He becomes a teacher and director of the Escuela Nacional de Bellas Artes (ENBA).

Under his pupils were Vinatea Reinoso, Camilo Blas, Enrique Camino Brent, Julia Codesido, Carlota (Cota) Carvallo, Jorge Segura, Aquiles Ralli, Gamaniel Palomino, Pedro Azabache Bustamante, Andrés Zevallos and Eladio Ruiz.

>Der peruanische Maler Jose Sabogal

>Der peruanische Maler Jose SabogalMost famous paintings

"Huanta", "Plaza de Huanta", "La Esmeralda de los Andes", "Plaza Serrana", "Caballo Nacional o Caballo de Paso", "Mujer en el Desierto (de Sechura)", "Manta Limeña" y "Mujeres del Ucayali" |

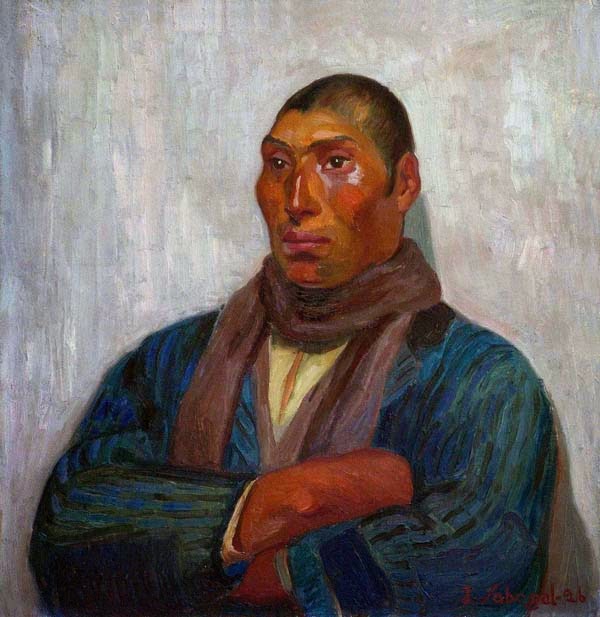

| El recluta |

Timeline

Sabogal was born 1888 in Cajabamba as a child of the mestizan family of Matías Sabogal (Spanish) and Manuela Diéguez de Florencia.Between 1908 and 1910 he visited Spain, the south of France, Italy extensively - living for a while in Rome - and the north of Africa before returning to America. He stays in Buenos Aires, Argentina.

From 1912 to 1913he studies at the National School of Art in Buenos Aires.

Between 1914 and 1917 he works as an art teacher in Jujuy, Argentina. There he meets the painter Jorge Bermúdez, a passionate lover of the rural life, who influenced Sabogal to promote indigenism.

1918 he lives for six months in Cuzco, Peru, where he paints the city with its inhabitants.

1919 the exhibition of his Cuzco paintings at the Casa Brandes in Lima draws attention to his work.

From 1920 to 1932 Sabogal taught at the Escuela Nacional de Bellas Artes (ENBA) in Lima becoming its first professor of painting.

1922 he exhibits his works in Mexico, making acquaintance with Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco and David Alfaro Siqueiros.

1922 he marries the writer María Wiesse Romero (1894-1964), daughter of the historian Carlos Wiesse Portocarrero, with whom he has two children: José Sabogal Wiesse (1923-1983) and Rosa Teresa Sabogal Wiesse (1925-1985).

1926 the first issue of the renowned magazine Amauta showed one of his works on its cover.

From 1932 to 1943 he was the second director of the Escuela Nacional de Bellas Artes (ENBA) - now Escuela Nacional Superior Autónoma de Bellas Artes del Perú (ENSABAP) < www.ensabap.edu.pe > - in Lima.

|

| El Indigena peruano |

The Humala administration continues to suck up to the USA and is preparing to copy Colombia and Mexico in their 'war on drugs'.

The Humala administration continues to suck up to the USA and is preparing to copy Colombia and Mexico in their 'war on drugs'.